In this documentary, London Film School continues a line of appraisals of Polari, often referred to as the “The Lost Language of Gay Men” (Baker, 2002).

This blog uses the documentary to question the representation of Polari, the causes of its death and its status as a gay language. But what was it and where did it come from?

Polari’s lattie

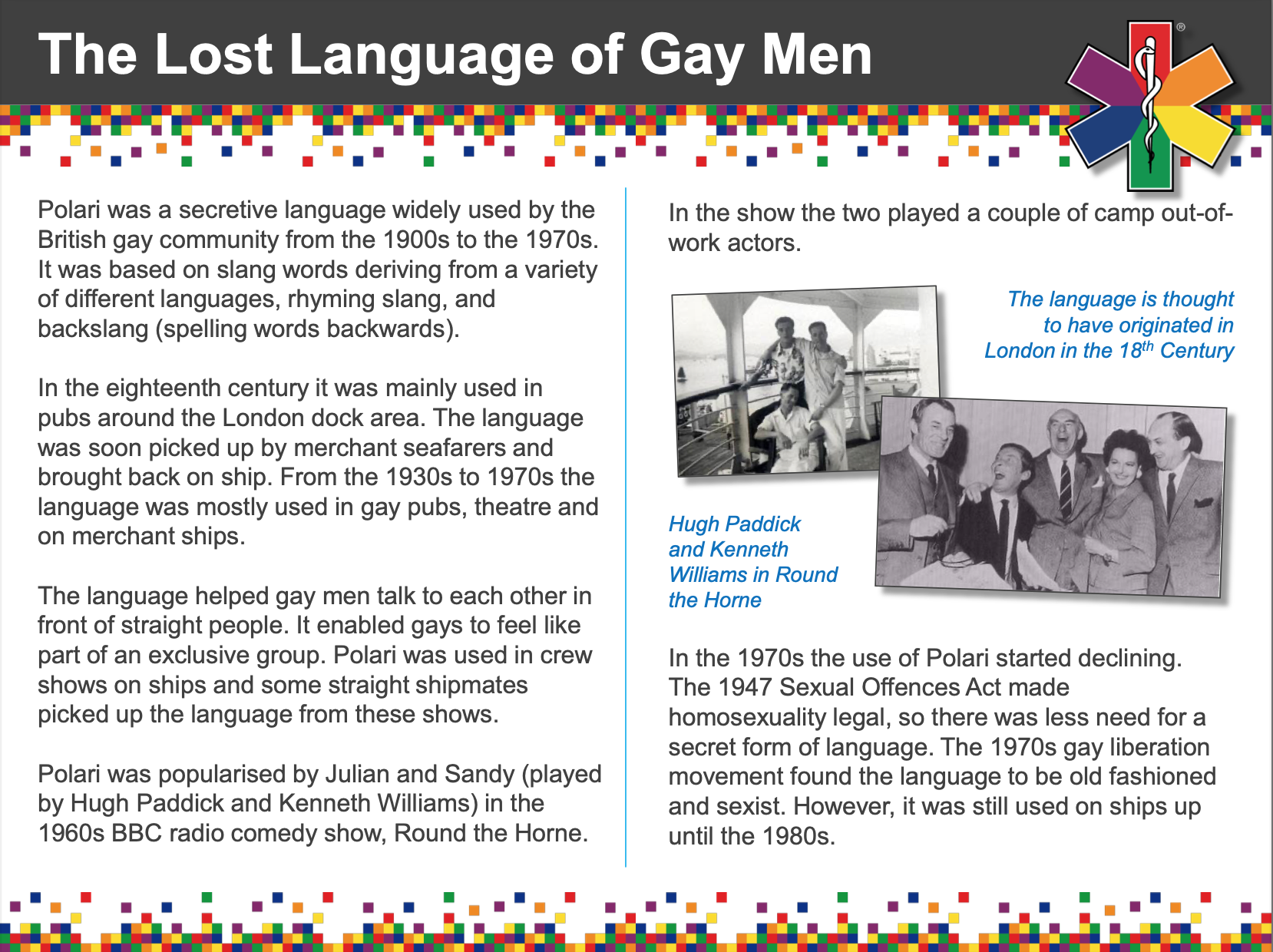

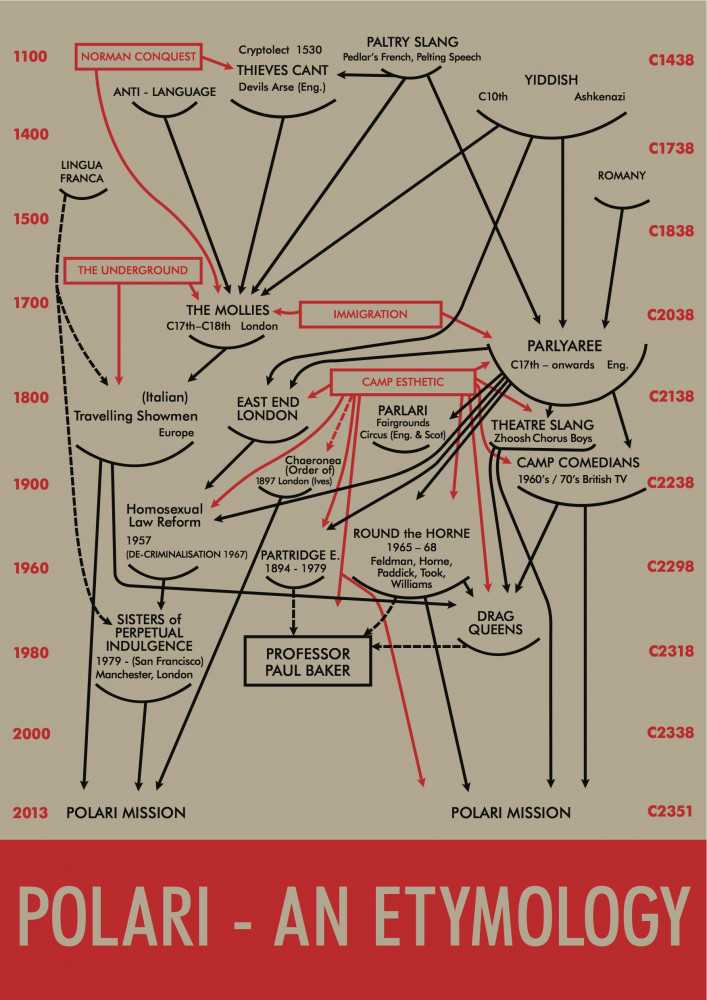

In the documentary, Baker identifies the roots of Polari in Molly Slang and Parlyaree, with numerous other influences. Hancock, building on Partridge emphasises the role of Lingua Franca, and notes “The connection with male…homosexual speech…through the sea and the theatre…”. (Hancock, 1984). Peter Scott-Presland, within the documentary further specifies “…defiantly feminine gay men…”.

Jez Dolan’s Polari – an Etymology According to a Diagrammatic by Alfred H. Barr (1936)

A dolly vocabulary

With a core of around 20 words and a vocabulary of up to 500 words, Polari, even its more complex East London variant, had limited uses, but made colourful use of what it had.

A Polari glossary http://chris-d.net/polari/ is helpful for translating this short film…

In the documentary, Baker explains that “Polari was something in between a slang and a full form of language”. He and Hancock explore this further, considering whether Polari was a dialect, slang, argot… before proposing that it was an anti-language, defined as:

“Special forms of language generated by some kind of anti-society…An anti-language serves to create and maintain social structure through conversation, just as an everyday language does; but the social structure is of a particular kind, in which certain elements are strongly foregrounded.” (Halliday 1976)

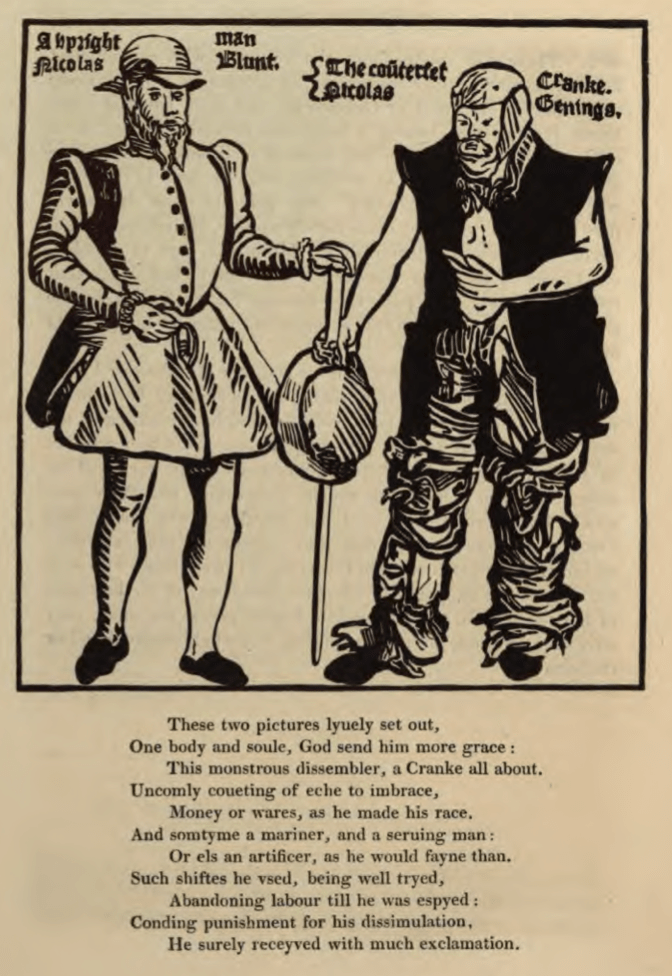

Illustration: A freshe water mariner or whipiacke. From “A caveat or warning for common cursetors, vulgarly called vagabonds” (Harman 1567)

Polari’s use as a code to be switched into for safety, talk of bodies and sex, and to create a community fits this description well, and is consistent with other sources: Cory recognised the usefulness of a “cantargot” for homosexuals to identify one another and communicate secretly and Leap sets out affective uses of “gay men’s English”.

Baker further brings Polari’s anti-social power to life within his presentation to Middle Temple’s LGBTQ+ group.

The documentary touches upon these secret situational, and affective uses of Polari. However, in simplifying Polari to a gay language, its richness is diminished, and the more powerful sense of an anti-language carving out space in a hostile environment to create an anti-society is almost absent.

The focus on one dimension is especially clear in accounts of Polari’s death.

Why did something so fantabulosa just troll off?

Polari’s death is typically attributed to four factors:

The Julian and Sandy sketches, 1965-8. The characters made (hilarious) use of Polari, undermining its use as a secret language.

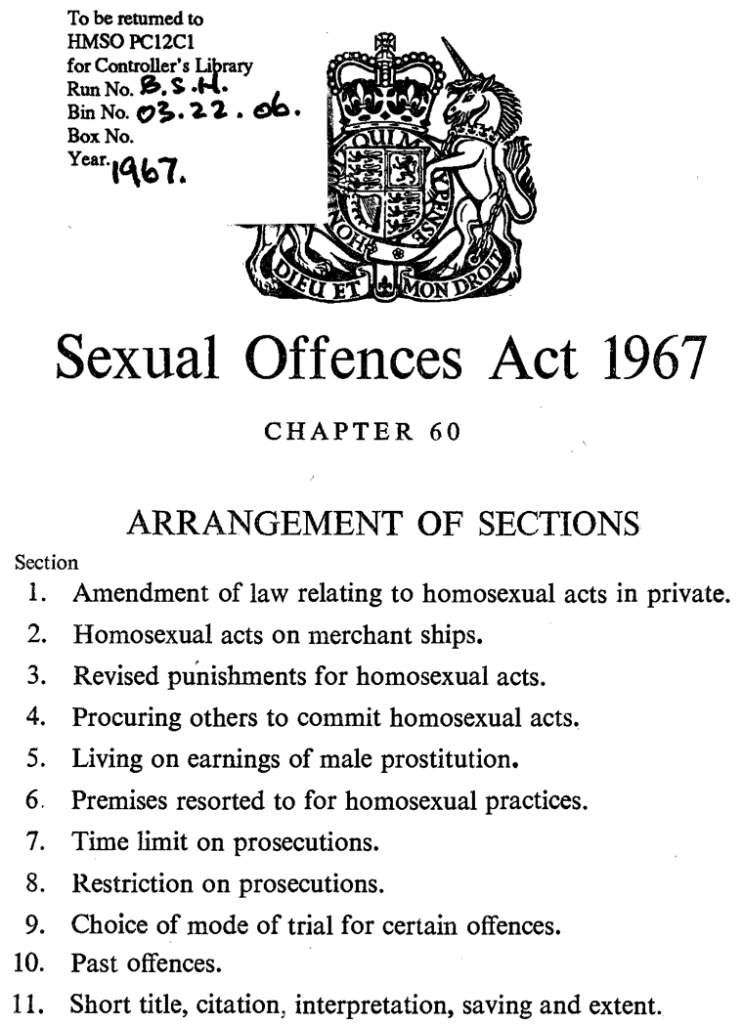

Decriminalisation of homosexuality for men over 21 in England & Wales.

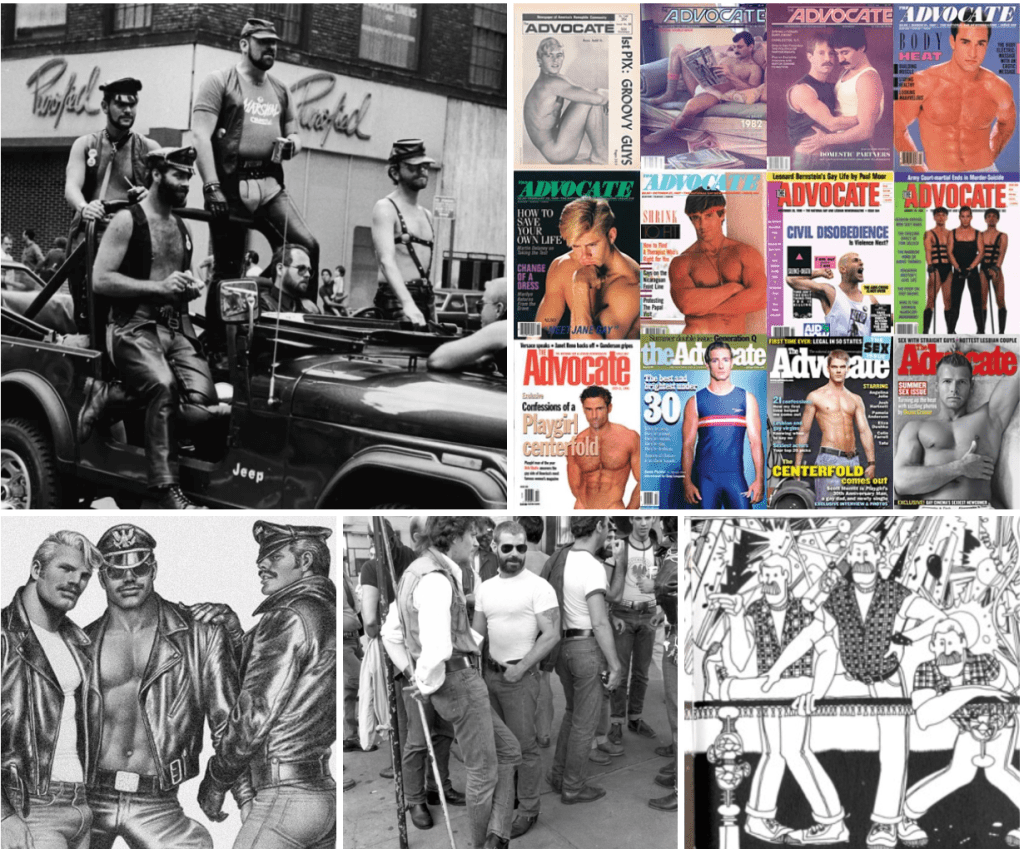

The rise of “masculine” gay archetypes.

These are all reasonable hypotheses, but even taken together they seem an incomplete and weak explanation for the death of a language with a history running back centuries.

Julian and Sandy ran for just three years.

Despite decriminalisation, persecution of gay men continued.

Camp gay men didn’t disappear.

The rise of gay liberation: moving from secrecy to pride, disdain for “Black Market Queens“, i.e. closeted men, by younger men, rejecting the identity surrounding Polari. These all have explanatory strength, but the speed of the language’s rapid decline warrants more scrutiny.

Trade

If the reasons for Polari’s demise are incomplete, what could be missing?

Baker and Hancock characterise Polari as largely a London language, and with two heartlands: theatre and seafarers; Baker considers East London Polari the most complex variety.

After the Second World War, London’s docklands declined, closing in 1981. Commercial shipping relocated, and cheap flights displaced the passenger cruisers with their concentration of gay workers (Baker and Stanley 2003).

A missing part of Polari’s story may be that a centuries’ old community all but disappeared, taking a language with it.

It seems reasonable to think that the upheaval in the industries which supported working class men on ships and docks, a significant part of Polari’s community of practice, contributed to its demise.

We’re all friends here duckie

Most histories of Polari position it as a gay language. However, Hancock groups Polari alongside Shelta, principally spoken by Irish Travellers, and in the video below it is placed in a family of London slangs.

Polari is the product of numerous intersecting worlds: male, English, homosexual, low status, theatre, trade networks…

By emphasising one aspect, accounts of Polari’s death may have missed at least one important factor, economic change. Others, such as men’s role in use of vernaculars, the impact of AIDS, and youth vs age could also be explored.

Taking this further, as Baker (2002) recognises, “gay” as a social construct would have been unrecognisable to most Polari speakers, at least until the 1960s. Polari’s characterisation as a gay language projects a modern construction of sexuality onto the past, with the risk of misrepresenting the anti-society formed by the language.

There are numerous languages used in a similar way to Polari, often grouped together as LGBT+/Queer: Tematicheskiy, a language born of suppression in Soviet era Russia, IsiNgqumo, a Bantu language from Southern Africa, Hijra & Koti Farsi from South Asia, Oxtchit, Israeli with words from largely non-Hebrew sources, Gayle, Bahasa Binan, Swardspeak, Lubunca, Pajubá …

Reframing Polari from a gay language, to one which is that and more, from a language which is different to Standard English, to a part of a web of Englishes may be an approach appropriate to understanding these other languages, and may help avoid the temptation to impose an alien framework upon them.

Coming soon! Where did the men working on passenger liners go next?: The language of trolley dollies*

*On “good” authority, the preferred expression is “tart with a cart”. Maybe Polari never did die, it just moved to Heathrow and took to the air.

References:

Baker, P (2002) Polari – The lost language of gay men. Routledge

Baker, P (2021) Interview with Paul Meier on In a manner of speaking podcast https://www.paulmeier.com/2021/02/01/episode-37-polari-the-secret-language-of-gay-men/February 2021 [accessed 30th November 2021]

Baker, P (2019) Interview with Daniel Midgley on Talk the Talk podcast http://talkthetalkpodcast.com/374-polari-britains-lost-gay-language/ at 27m 45sec [accessed 29th November 2021]

Baker, P http://wp.lancs.ac.uk/fabulosa/ [accessed 15th November 2021]

Baker, P and Stanley, J (2015) Hello Sailor! The hidden history of gay life at sea. Rotledge. Chapter 3, Speaking gay secrets

Cory, D (1951) “Take my word for it” Chapter 2 of The Language and Sexuality Reader, Cameron, D and Kulick, D (2006) Routledge

Halliday, MAK (1976) Anti-Languages American Anthropologist , Sep., 1976, New Series, Vol. 78, No. 3 (Sep., 1976), pp. 570-584, Wiley

Hancock, I (1979) Shelta and Polari Chapter 24 of Language in the British Isles, Trudgill, P (1984) Cambridge University Press

Holmes and Wilson (2017) An introduction to sociolinguistics, 5th Edition, Routledge, pp80-103, 203-213, 344-345

Leap, W (1999) “Can there be gay discourse without gay language?” Chapter 8 of The Language and Sexuality Reader, Cameron, D and Kulick, D (2006) Routledge

Partridge, E (1933) Slang today and yesterday, Republished 2015, pp247-251, Routledge & Kegan Paul